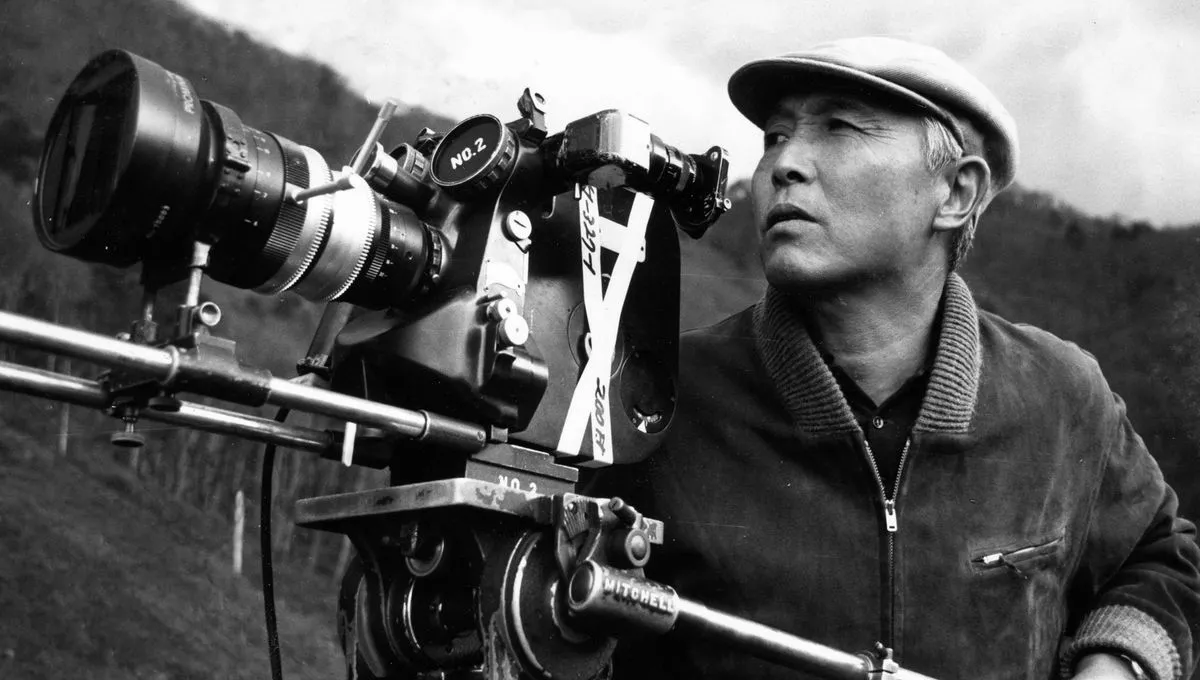

For the past week the Bay Area has played host to a Godzillathon taking place at Viz Cinema in San Francisco’s Japan Town. This Godzilla film festival started on May 5th and ends tonight on May 13th with a showing of Yoshimitsu Banno’s film Godzilla vs. Hedorah (1971). The Godzillathon coincided with what would have been film director and writer Ishiro Honda’s 99th birthday on May 7th. Honda directed the original Godzilla film but he was also responsible for many other popular science fiction and fantasy films produced in Japan.

I wasn’t able to attend the spectacular Godzillathon event so I consoled myself by spending my time reading Peter H. Brothers’ recent book, Mushroom Clouds and Mushroom Men: The Fantastic Cinema of Ishiro Honda. This 282 page volume chronicles the life and films of one of Japan’s most beloved and prolific filmmakers. Although Honda’s name is legendary in Japan, the director is still relatively unknown in the US. One reason for this is the lack of information that has been readily available about Honda in English. Peter H. Brothers has set out to change that with Mushroom Clouds and Mushroom Men: The Fantastic Cinema of Ishiro Honda, which is the first English language book about this important Japanese director.

Brothers’ begins his examination of Ishiro Honda with a thoughtful look at his long career behind the camera before delving into the director’s life and reviewing his films. Although Honda is mainly known as the filmmaker behind the original Godzilla film, he made an incredible 82 movies during his lifetime as well as documentary shorts and directed episodes of popular Japanese television programs such as Ultraman Returns Zone Fighter. Honda also collaborated with the acclaimed filmmaker Akira Kurosawa on six of his films including Stray Dog (1949), Ran (1985), Dreams (1990), Rhapsody in August (1991) but the book limits its focus to Honda’s contributions to science fiction and fantasy cinema, which was the director’s specialty.

The book details Honda’s working relationship with Toho Studios as well as his longtime producer Tomoyuki Tanaka, special effects guru Eiji Tsuburaya and composer Akira Ifukube. It also offers readers an inside look at Honda’s directing and writing methods that were integral to the success of his films. The author doesn’t shy away from delving into the technical aspects of Honda’s work but the book never comes across as a dry academic read. It’s obvious that Peter H. Brothers is first and foremost a fan of Honda’s films and I appreciated his personal perspective on the director.

Throughout Ishiro Honda’s long career he considered himself a documentary filmmaker who shot “natural dreams.” Honda’s observational approach to filmmaking is reflected in the narrative structure of his movies as well as the personal way that he shot them. Honda wasn’t all that interested in scaring his audience and the monsters in his films were usually depicted as sympathetic creatures. Villains were almost completely absent from Honda’s work. He genuinely believed that there were no evil people in the world; only unfortunate circumstances that made people (or monsters) act against their own interests as well as humanities. The director also rarely choose to focus on one or two main characters since he was much more concerned with group dynamics. Individuals were usually forced to unite and act together in order to stop the rampaging monsters. The absence of lone heroes and villains from Honda’s monster movies made them very different from their American counterparts. Honda also liked to shoot on location whenever possible and he spent a surprising amount of time filming unknown actors and extras who were featured in crowd and reaction shots or as part of the military force trying to save the Japanese public from whatever disasters were taking place.

Honda’s life is as fascinating as the films he made and the book provides readers with an interesting look at the man behind the movies. Beginning with Honda’s humble beginnings as the son of a priest, through his college years and his harrowing experiences as a solider in the Japanese military during WW2, Brothers’ book smartly illustrates how Honda’s experiences shaped his films and dictated his approach to directing. The book is sadly missing any images that would have greatly enhanced my own reading experience but he colors it with interview outtakes and quotes from Honda himself that really add to the book’s personal approach. Honda’s own words make it obvious that the director was an extremely modest man who was never completely satisfied with the films he made. The budget limitations of the Japanese studio system often worked against his creative impulses and throughout most of his life Honda wasn’t fully aware of how much his work had inspired and influenced audiences around the world.

“I try to express in my films things that no other art can approach. In my monster films for example, I use special effects in the same way one would use a special film stock, a special camera, and so on. Monster films permit me to use all of these elements at the same time. They are the most visual kind of film.”

– Ishiro Honda, Mushroom Clouds and Mushroom Men: The Fantastic Cinema of Ishiro Honda

The book ends with reviews of the 25 fantasy and science fiction films that Honda directed during his lifetime including Godzilla (1954), Rodan (1956), The Mysterians (1957), Mothra (1961), King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962), Matango (1963), Mothra vs. Godzilla (1964), Frankenstein vs. Baragon (1965), The War of the Gargantuas (1966), Destroy All Monsters (1968), Latitude Zero (1969) and his last film, Terror of Mechagodzilla (1975). The autor’s enthusiasm for his subject is apparent on every page and I appreciated his thoughtful insights into Honda’s work. He also has a good sense of humor and knows when to inject some fun into his writing. Most of Honda’s science fiction and fantasy films have become available on DVD in recent years so the book indirectly provides readers with a helpful guide to these movies if you plan to rent or purchase them. After reading Mushroom Clouds and Mushroom Men: The Fantastic Cinema of Ishiro Honda I was inspired to re-watch some of Honda’s films myself and I definitely felt as if I was seeing them through a new set of eyes thanks to Brothers’ book.

Mushroom Clouds and Mushroom Men: The Fantastic Cinema of Ishiro Honda is a welcome addition to the new batch of books released in the last 5 years discussing the importance of Godzilla such as August Ragone’s Eiji Tsuburaya: Master of Monsters, William M. Tsutsui’s Godzilla on My Mind: Fifty Years of the King of Monsters and David Kalat’s A Critical History and Filmography of Toho’s Godzilla Series. What separates Brothers’ book from the rest is its concentration on the director of the films instead of the special effects or the monster. In the future I would love to see Brothers release a revised addition of his book that covers all of Honda’s films and delves even deeper into his directing career. Peter H. Brothers self-published his book and I applaud his efforts. He brings 30 years of writing experience and a lifetime of interest in Honda’s movies to his work. Anyone who is interested in learning more about the director and his films will find Mushroom Clouds and Mushroom Men: The Fantastic Cinema of Ishiro Honda a worthwhile read.