Godard by Solanas, Solanas by Godard

Fernando Solanas, one of the most important political filmmakers in Latin America and the world, has passed away. As a tribute, we published a dialogue between Solanas and the French film master Jean-Luc Godard in October 1969

INTERVIEWS By Jean-Luc Godard

Godard: How would you define this film ("The Hour of the Furnaces")?

Solanas: Like a film-essay, ideological and political. Some have spoken of film-book and this is correct, because together with the information, we provide reflexive elements, titles, didactic forms... The narrative structure itself is built like a book: prologue, chapters and epilogue. It is an absolutely free film in its form and its language: we take advantage of everything that is necessary or useful for the purposes of knowledge that the work proposes. From direct sequences or reports to others whose formal origin is located in stories, tales, songs or montage of "image-concepts". The subtitle of the film sets its tone as a document, proof of a reality: Notes and Testimonies on Neocolonialism, Violence and Liberation. It is a cinema of denunciation, documentary, but at the same time it is a cinema of knowledge and investigation. A cinema that contributes, above all, in its directionality, because it is not aimed at everyone, at an audience of "cultural coexistence", but rather it is aimed at the great masses who suffer from neocolonial oppression. This is especially true in parts two and three, because the first narrates what the masses know, intuit and live and plays in the work as a great prologue. La Hora de los Hornos is also a film-act, an anti-show, because it denies itself as a cinema and opens itself to the public for its debate, discussion and development. The projections become spaces of liberation, in "acts" where man becomes aware of his situation and the need for a deeper praxis to change that situation. to an audience of "cultural coexistence", but is directed at the great masses who suffer from neocolonial oppression. This is especially true in parts two and three, because the first narrates what the masses know, intuit and live and plays in the work as a great prologue. La Hora de los Hornos is also a film-act, an anti-show, because it denies itself as a cinema and opens itself to the public for its debate, discussion and development. The projections become spaces of liberation, in "acts" where man becomes aware of his situation and the need for a deeper praxis to change that situation. to an audience of "cultural coexistence", but is aimed at the great masses who suffer from neocolonial oppression. This is especially true in parts two and three, because the first narrates what the masses know, intuit and live and plays in the work as a great prologue. La Hora de los Hornos is also a film-act, an anti-spectacle, because it denies itself as cinema and opens itself to the public for its debate, discussion and development. The projections become spaces of liberation, in "acts" where man becomes aware of his situation and the need for a deeper praxis to change that situation. they intuit and live and play in the work as a great prologue. La Hora de los Hornos is also a film-act, an anti-spectacle, because it denies itself as cinema and opens itself to the public for its debate, discussion and development. The projections become spaces of liberation, in "acts" where man becomes aware of his situation and the need for a deeper praxis to change that situation. they intuit and live and play in the work as a great prologue. La Hora de los Hornos is also a film-act, an anti-show, because it denies itself as a cinema and opens itself to the public for its debate, discussion and development. The projections become spaces of liberation, in "acts" where man becomes aware of his situation and the need for a deeper praxis to change that situation.

Godard: How is the act performed?

Solanas: In the film there are pauses, interruptions, so that the film and the proposed themes go from the screen to the audience, that is, to the live, present fact. The old spectator, the subject in expectation, according to the traditional cinema that developed the eighteenth-century conceptions of bourgeois art, this non-participant, becomes a living protagonist, a real actor in the history of the film and of history itself. , since the film is a film about our contemporary history. And a film about liberation, about an unfinished stage in our history, can only be an unfinished film, a film open to the present and the future of liberation. That is why the film must be completed and developed by the protagonists and we do not rule out the possibility of adding new notes and film testimonies, if in the future there are new facts that need to be incorporated. The “acts” end when the participants decide to do so. The film has been the trigger for the act, the mobilizer of the old spectator. On the other hand, we believe that of Fanon who says «If it is necessary to engage the whole world in the fight for common salvation, there are no clean hands, there are no spectators, there are no innocents. We all get our hands dirty in the swamps of our soil and in the emptiness of our brains. Every spectator is a coward or a traitor. In other words, we are not facing an expression-cinema, nor a communication-cinema, but rather an action-cinema, a liberation cinema. we believe that of Fanon who says «If it is necessary to engage the whole world in the fight for common salvation, there are no clean hands, there are no spectators, there are no innocents. We all get our hands dirty in the swamps of our soil and in the emptiness of our brains. Every spectator is a coward or a traitor. In other words, we are not facing an expression-cinema, nor a communication-cinema, but rather an action-cinema, a liberation cinema. we believe that of Fanon who says «If it is necessary to engage the whole world in the fight for common salvation, there are no clean hands, there are no spectators, there are no innocents. We all get our hands dirty in the swamps of our soil and in the emptiness of our brains. Every spectator is a coward or a traitor. In other words, we are not facing an expression-cinema, nor a communication-cinema, but rather an action-cinema, a liberation cinema.

The time of the ovens

Godard: How did you go about doing it?

Solanas: Working and overcoming on the fly all the difficulties that were presented to us: economic, technical, artistic… The needs of the work were determining a method and a way of working. Like most of the most recent independent Argentine cinema, it is made with minimal equipment, making very few, everything. At the same time, he worked in advertising cinema to pay for basic laboratory and film expenses. We use 80% of the film 16 mm cameras. and between two or three we have carried out almost all the technical and productive tasks, in addition to having the generous support of numerous friends and colleagues and townspeople, without whom it would have been impossible to make these four and thirty hours of film.

Godard: The film I'm starting now, The Strike, will be made by four people: my wife in acting, me in sound, a cameraman and his wife in editing. I do it with this little television camera…

Solanas: Today the myth has been destroyed that the quality of expression was the heritage of the industry, of great teams, of technical mysteries... We could also say that the advancement of cinematographic technique is also liberating cinema...

Godard: What problems did they have?

Solanas: Aside from the problems common to all economic production work, I could tell you that the biggest problem to overcome was dependence on foreign film models. That is, free ourselves as creators. It is this fundamentally aesthetic dependence of our cinema on American and European cinema that is its great limitation. And this could not be understood apart from the analysis of the Argentine cultural situation. The official Argentine culture, the culture of the neocolonial bourgeoisie, is a culture of imitation, second-hand, old and decadent. Culture built on the cultural models of the oppressive, imperialist bourgeoisie. Culture to the "European", today Americanized. For this reason, most of Argentine cinema is built on the productive, argumentative and aesthetic model, of the Yankee cinema or the so-called European “auteur” cinema. There is no invention or own search. There is translation, development or copy. There is dependency...

Godard: American cinema, cinema to sell...

Solanas: Exactly, a cinema linked to entertainment, to business; subordinated and conditioned by capitalist exploitation. From this profit motive, in production, all the genres, techniques, languages and even duration that cinema has today are born. And it was breaking with this conception, with these conditions, which gave us the most work. We had to free ourselves: cinema made sense if we could use it with the freedom with which a writer or a painter goes about their work, if we could make our experience based on our needs. And so we decided to risk, try, search, rather than condition ourselves to the "masters" of the so-called "seventh art", who only expressed themselves through the novel, the story or the theater. We begin to free ourselves from “viscontis, renoires, giocondas, resnais, paveses” etc… willing to find our way, our language, our structure... that which coincides with the needs of communication to our public and with the needs of the total liberation of the Argentine man. That is to say, this search did not arise only from a cinematographic search, it did not arise as an aesthetic category, but as a category of the liberation of ourselves and of the country. This is how a film was born that abandoned the props of the plot-novel or the actor, that is, a cinema of stories, of feelings, to make a cinema of concepts, thoughts, themes. The fictionalized history gave way to a story told with ideas, to a cinema to see and read, to feel and think, an investigative cinema equivalent to an ideological essay... our structure… that which coincided with the needs of communication to our public and with the needs of the total liberation of the Argentine man. That is to say, this search did not arise only from a cinematographic search, it did not arise as an aesthetic category, but as a category of the liberation of ourselves and of the country. This is how a film was born that abandoned the props of the plot-novel or the actor, that is, a cinema of stories, of feelings, to make a cinema of concepts, thoughts, themes. The fictionalized history gave way to a story told with ideas, to a cinema to see and read, to feel and think, an investigative cinema equivalent to an ideological essay... our structure… that which coincided with the needs of communication to our public and with the needs of the total liberation of the Argentine man. That is to say, this search did not arise only from a cinematographic search, it did not arise as an aesthetic category, but as a category of the liberation of ourselves and of the country. This is how a film was born that abandoned the props of the plot-novel or the actor, that is, a cinema of stories, of feelings, to make a cinema of concepts, thoughts, themes. The fictionalized history gave way to a story told with ideas, to a cinema to see and read, to feel and think, an investigative cinema equivalent to an ideological essay... it did not emerge as an aesthetic category, but as a category of the liberation of ourselves and the country. This is how a film was born that abandoned the props of the plot-novel or the actor, that is, a cinema of stories, of feelings, to make a cinema of concepts, thoughts, themes. The fictionalized history gave way to a story told with ideas, to a cinema to see and read, to feel and think, an investigative cinema equivalent to an ideological essay... it did not emerge as an aesthetic category, but as a category of the liberation of ourselves and the country. This is how a film was born that abandoned the props of the plot-novel or the actor, that is, a cinema of stories, of feelings, to make a cinema of concepts, thoughts, themes. The fictionalized history gave way to a story told with ideas, to a cinema to see and read, to feel and think, an investigative cinema equivalent to an ideological essay...

The time of the ovens

Godard: What role can this cinema play in the liberation process?

Solanas: First of all, transmit the information that we don't have. The media, the apparatuses of culture, are in the hands or controlled by the system. The information that is disseminated is that which the system is interested in. The role of a cinema of liberation is, above all, to elaborate and spread our information. Once again raise that of: theirs and ours. On the other hand, the entire conception of our cinema – open cinema, participatory cinema, etc. …– points to a single and fundamental objective: to help to let go, to liberate man. An oppressed, repressed, inhibited, mediated man. It is a cinema made for this fight. Increase the awareness and knowledge of the most restless layers of the Argentine people. Will it be able to reach only small nuclei? It's possible. But the so-called mass cinema, it only transmits what the system allows, that is, it becomes one more instrument of evasion or mystification. Liberation cinema, on the other hand, reaches smaller groups at this stage, but it reaches in depth. Come with the truth. It is better to transmit ideas that help liberate a single man than to contribute to the massive colonization of the people.

The time of the ovens

Godard: Cubans say that the duty of the revolutionary is to make the revolution: What is the duty of the revolutionary filmmaker?

Solanas: Using cinema as a weapon or a rifle, turning the work itself into a fact, into an act, into a revolutionary action. What is this duty or commitment for you?

Godard: Work fully as a militant, make fewer films and be more militant. This is very difficult because the filmmaker here has been educated in individualism. But also in cinema it is necessary to start over...

Solanas: Your experience after "May" is limit, I want you to pass it on to our Latin American colleagues...

Godard: “Mayo” has been a fantastic release, for many of us. “Mayo” has imposed its truth on us, it has forced us to speak and pose the problems in another way. Before "May", here in France, all intellectuals had alibis that allowed them to live well, to have a car, an apartment... but "May" has created a very simple problem, the problem of having to change their lives, of breaking with the system. To the intellectuals who had been successful, "May" put them in a situation analogous to that of a worker who must abandon the strike because he owes the grocer four months. There are filmmakers like Truffaut, who sincerely say that they are not going to change their lives, and others who continue to play a double game, like those of “Cahiers…”

Godard in May 68

Solanas: Are you still in “Cahiers du Cinéma”?

Godard: No, I've left completely since they supported the Venice Film Festival (68) despite the boycott that Italian filmmakers had started... It's not that I'm against filmmakers getting together, but I'm against what they are until today the festivals…

Solanas: Have you renounced the benefits that the system gave you?

Godard: Yes sir. I realized that I was oppressed, that there is much less intellectual repression than physical repression, but that it also makes its victims and then I felt oppressed... the more I wanted to fight, the more they squeezed my neck to silence me and also I completely self-repressed myself...

Solanas: It is the situation that every filmmaker in Latin America suffers... with the aggravating circumstance that there are much tougher censorship laws and even crimes of opinion, as in Brazil and Argentina... Today the situation of the filmmaker is so grotesque, that the fields and options. If the filmmaker delves into any topic, be it love, family, relationship, work, etc... he reveals the crisis of society, he shows the truth naked. And the truth, given the political temperature of our continent, is subversive. For this reason, the filmmaker is condemned to self-repression, self-censorship, self-castration creatively and continues the impossible game of being an "author" within the system, or breaking with it and trying his own independent path. Therefore, today there are no options: either the truth of the system is accepted, that is, his lie is accepted; or the only truth is accepted, which is the national truth. And that is defined through the works: or complicity with the regime, through aseptic films; or total liberation…

Godard: It's true that in France it's much easier to make a film than in Greece or Argentina... In Greece, if you don't do exactly what the board of colonels wants, they immediately introduce the police and repression. But in France there is a soft fascism that after May has become harsher... This soft fascism is the one that returns you to your country of origin if you are a foreigner or the one that sends you to a distant destination if you are a professor at the Sorbonne …

Solanas: So what is the situation of French cinema, of European cinema? …

Godard: I would say that there is no European cinema, but there is an American cinema everywhere. Just as there is not an English industry but an American industry that works in England; Just as you have said that there is no Argentine culture, but rather a European-American culture that is produced through Argentine intermediaries... there is also no European cinema, but rather an American cinema... In the silent era... A German film is not It looked like an Italian or French silent film. Today there is no difference between an American, a German or an Italian film… You work in co-productions… Italian westerns, American films shot in Russia… Everything is domesticated by the United States, everything is Americanized… and what do I mean by Americanized? … that all European cinema is a cinema made for nothing more than selling itself, to make money. Even arthouse cinema. This is what falsifies everything… Even in Russia, even if it is distributed in film clubs, it is made to be sold through the politburo bureaucrats. In other words, it is exactly the same… In this way, a film is not born from the specific analysis of a specific situation, but is something else…

Sunshine: What is…?

Godard: Look… it is an individual imagination, which is sometimes very generous or very “left”… which is fine… but it is made to be sold because it is the only way for this imagination to continue to function and sell. That is why there are no differences between Antonioni, Kazan, Dreyer, Bergman... and a bad filmmaker like Delannoy, in France... There are differences in quality but not in substance: they all make films of the ruling classes... that is what I have done for ten years ... even if my intention was different ... But I have been used for the same.

Solanas: Does the so-called European auteur cinema today continue to be critical, contestational or advanced cinema...?

Godard: At some point, here in Europe, for each author it was… But then it was necessary to go further and this has not evolved. The notion of “author” was a revolution in the times when the author fought against the producer, a bit in the way that a bourgeois fought against a gentleman in the Middle Ages. Now the bourgeois has become a lord, the author has replaced the producer. Therefore, an auteur cinema is no longer needed, because the more it is a cinema at the level of the bourgeois revolution. In other words, cinema today is a very reactionary medium. Even American literature is much less reactionary than American cinema...

Solanas: Is the author a category of bourgeois cinema?

Godard: Exactly. The author is something like the professor at the university...

Solanas: How do you define this auteur cinema ideologically?

Godard: Objectively, today it is a cinema allied with reaction.

Solanas: What are your examples?

Godard: In France, me before “May”; Truffaut, Rivette, Demy, Resnais… everyone… In England Lester, Brooks… in Italy, Pasolini, Bertolucci… well… Polanski… everyone…

Solanas: Do you consider that these filmmakers are integrated into the system?

Godard: Yes. They are integrated and they don't want to disintegrate...

Solanas: And the most critical cinema, is it also recovered by the system?

Godard: Yes, these works are recovered by the system because they are not strong enough in relation to their integrating power. For example, the American “Newsreels” are as poor as you or me, but if CBS offered them $10,000 to screen one of their films, they would refuse because they would be integrated… And why would they be integrated?… Because the structure of the American television is so strong that it recovers for the system everything it projects. The only way to “answer” the television system in the United States would be to show absolutely nothing for two or four hours, which television pays just to show and “recover”. And in Hollywood now a film about Che Guevara is being prepared and there is even a film with Gregory Peck about Mao Tse-tung... Those Newsreels films,

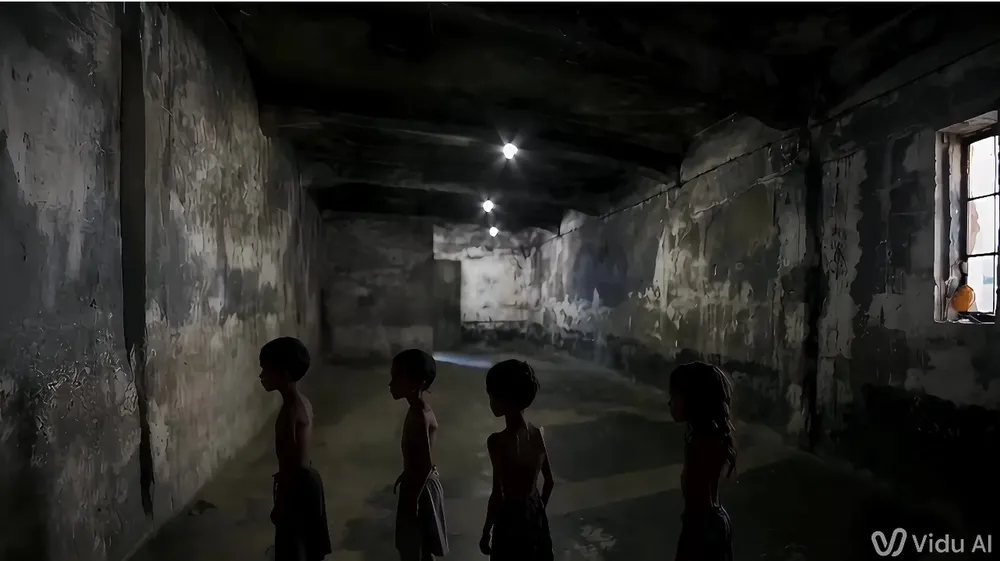

Top: Black Liberation (Eduard de Laurot, 1967) Bottom: Ice (Robert Kramer, 1970)

Solanas: I don't agree with the last thing you say. I think that when a national film deals with an issue from the point of view of the oppressed classes, when it is clear and deep in this aspect, it becomes practically indigestible for the system… I do not think that CBS would buy a film about “Black Power ” or with Carmichael haranguing blacks about violence or that French television would show a film with Cohn Bendit saying everything he thinks… In our countries, many things are allowed when they refer to foreign problems, but when these same problems are due to their political nature, they cannot be absorbed either... A few months ago, Argentine censorship banned Eisenstein's Strike and October... For the rest, most European auteur cinema,

La chinoise (Jean-Luc Godard, 1967)

Godard: Okay, but when the political situation here in France becomes difficult for them, they can no longer recover as before... This is the case of your film, which I am sure they will not be able to recover and will be banned... But it is not only in political aspect of recovery, but also aesthetically. The most difficult films of mine to recover are the last ones I made in the system, where aesthetics have become political… like Week-End and La chinoise… A political position must correspond to an aesthetic position. It is not an auteur cinema that must be made, but a scientific cinema. Aesthetics must also be studied scientifically. All research, in science as in art, corresponds to a political line, even if you ignore it. Just as there are scientific discoveries, there are also aesthetic discoveries. For this reason, it is necessary to be consciously clear about the path that has been chosen and to which one is committed. Antonioni, for example, once did valid work, but now he no longer does. He has not radicalized. He makes a film about students, as it could be done in the United States, but he doesn't make a film that comes from the students... Pasolini is talented, very talented, he knows how to make films about topics such as learning to make compositions at school... For example, you can make a beautiful poem about the Third World… but it is not the Third World that has made the poem. So, I believe that it is necessary to be the Third World, to participate in the Third World and then one fine day it is the Third World that sings in the poem and if you are the one who does it, it is simply because you are a poet and you know how to do it. … As you say, a film must be a weapon, a rifle... but there are still certain people who are at night and need more of a pocket flashlight to illuminate their surroundings and this is precisely the role of theory... A Marxist analysis of the problems is needed of image and sound. When Lenin himself dealt with cinema, he did not make a theoretical analysis, but rather an analysis in terms of production, so that there would be cinema everywhere. Only Eisenstein and Dziga Vertov dealt with the subject. so that there would be cinema everywhere. Only Eisenstein and Dziga Vertov dealt with the subject. so that there would be cinema everywhere. Only Eisenstein and Dziga Vertov dealt with the subject.

Solanas: How do you film now, do you have a producer?

Godard: I never had a producer. I had one or two producers that I was friends with, but I never worked with normal production houses. When I did it once or twice, it was by mistake… For me, now it's impossible. I don't know how the others do. I see colleagues of mine, like Cournot or Bertolucci, for example, who are forced to ring the doorbell at a cretin's house and argue. Accept arguing with a cretin to save your work. But I never did this. Now I am the producer, with what I can… and I film much more than before, because I film in a different way, in 16 mm., or with my small television crew… And also differently, in another sense, although it seems pedantic to use the Vietnamese example. I am referring to the use that the Vietnamese give to the bicycle in combat or in the resistance. Here a champion cyclist would not know how to use a bicycle at all as a Vietnamese does. Well, I want to learn to use a bicycle like a Vietnamese does. I have a lot to do with my bike, a lot of work ahead of me and that is what I have to do. That's why I film a lot now. This year I made four films…

Solanas: What is the difference between the movies you made before and the movies you make now?

Godard: Now I try to make a cinema that consciously tries to participate in the political struggle. Before, I was unconscious, sentimental... I was on the left, if you will, although I started from a right-wing position and also because I was a bourgeois, an individualist. Later, I moved sentimentally towards the left, until I reached a position not of a "parliamentary" left, but of a revolutionary, radicalized left, with all the contradictions that this imposes...

Solanas: And cinematographically?

Godard: Cinematographically, I have always tried to do what was never done, even when working with the system. Now I try to link "what is not done" with the revolutionary struggles. Before, my search was an individualistic struggle. Now I want to know if I'm wrong, why I'm wrong and if I'm right, why. I try to do what is not done, because what is already done, in cinema, is practically all imperialist. Eastern cinema is an imperialist cinema; Cuban cinema –apart from Santiago Álvarez and one or two documentarians– is a cinema that works halfway on an imperialist model. All Russian cinema quickly became imperialist or bureaucratized, except for two or three people who have fought against it: Eisenstein, Dziga Vertov and Medvedkin, which is not known at all… Now I make movies with the workers and I do what they ideologically want, but I also tell them: “be careful!”… it is necessary that in addition to making this movie, they do not go on Sunday to consume the system cinema. This is our duty and the way to help “the fight of the filmmakers…” In summary, I have come to the conclusion that since the panorama of cinema is very complicated and confusing, it is necessary to make films with people who are not filmmakers, with people who are interested in what they see on the screen being related to themselves...

Now! (Santiago Alvarez, 1965)

Solanas: Why do you work with people who are not from the cinema?

Godard: Because regarding the language of cinema, it is a small handful of individuals, in Hollywood or Mosfilm or wherever, who impose their language, their discourse, on the entire population and it is not enough to get out of that small group and say “ I make a different type of cinema”…because you always have the same ideas about cinema. Therefore, to overcome this, we must give the opportunity to make the cinematographic speech to people who until now had no opportunity... An extraordinary thing about last "May", in Paris, was when all the people began to write on the walls... The only one who had the right to write on the walls was advertising... People were made to believe that writing on the walls was dirty and ugly, but I also had the impulse to write about walls and I've been doing it since “May”… It was no longer an anarchic or individualistic idea but rather a deep desire… Also for cinema it is necessary to start over. I made a film with students who talked to workers and it was very clear: the students talked all the time, the workers never... The workers talk to each other a lot... but where are their words?... Neither in the newspapers, nor in the films , there are the words of the people who make up 80% of humanity... We have to force the minority that has the floor to give it up to 80%, make sure that the word of the majority can be expressed. That's why I don't want to belong to the minority that talks and talks all the time or to the one that makes movies, but I want my language to express 80%... and that's why I don't want to make movies with people from the movies,

Solanas: What is the idea of La Huelga, your next film?

Godard: It is a woman who tells a strike. She has a boy and that's why she tells from her home, what a week of strike is like and also the relationship between sex and work. When you work ten hours a day, whether you are an intellectual or a worker, you cannot make love... and if the woman is the one who stays at home, the opposite can happen... this situation poses many problems and here we really talk about these things. I will do all this film with my television camera. It is very economical and practical. Right here we film and we immediately see what we have done, in image and sound, without depending on the laboratory, editing, etc... If we don't like it, we do it again... I will do almost the entire film in a single shot. The work will be in the book, in the dialogue.

Solanas: And then how do you project it?

Godard: It's going to be shown on televisions in neighborhood cafes, in manufacturing areas... People discuss and talk about it, and that mere fact means moving forward for everyone.

Solanas: What role can cinema play in the liberation process?

Godard: A fundamental role. As you said, inform and immediately reflect on that information… You have to make clear and simple films that help clarify things… And simple films from a technical point of view because the technique is very expensive. If synchronization or editing are very expensive when we film, let's work with few shots or with voiceover... and if they are unavoidable, let's do them, but keep in mind that it is necessary to simplify. Nothing more.

Originally published in Third World Cinema, Year 1, No. 1, October 1969, pp. 48-63.