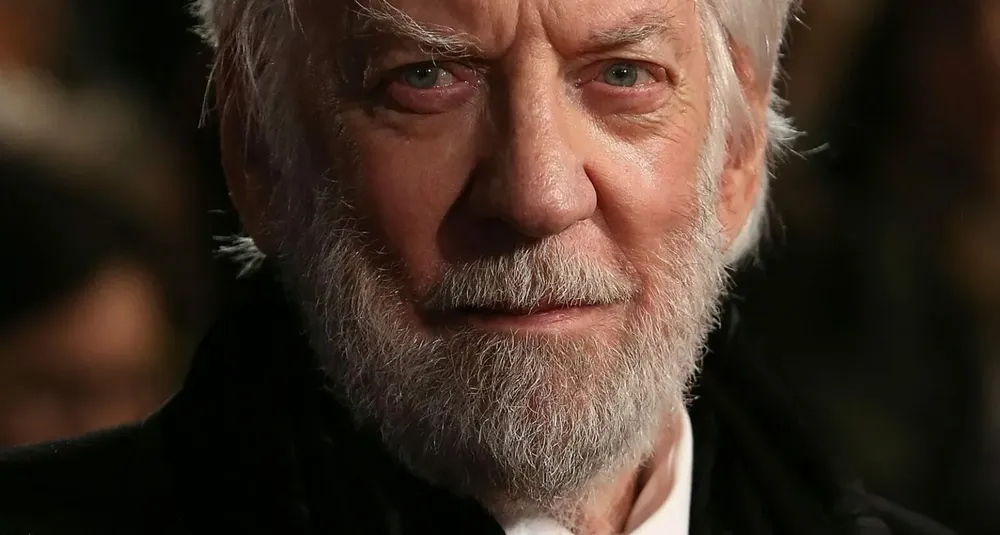

Last Thursday, June 20, the chameleon actor Donald Sutherland died in Miami. The actor, of Canadian origin, leaves behind a legacy of almost two hundred appearances in film and television, where his charisma, versatility and professionalism always shone. Hollywood did not appreciate in time one of the great actors of his generation, and wanted to compensate his blindness with an honorary Oscar, which was delivered to him in 2017. In an emotional speech, brimming with lucidity and a sense of humor, he thanked the characters he had played throughout his career, thanking them for having used their lives to talk about their own lives.